The middle of winter can seem like the very bleakest of times! Much of the bounty of the autumn months has passed and in early January the weather does much to deter even the most ardent foragers. However, for those who still dare to venture out and seek the sheltered spots a pleasant surprise awaits. The youngest and tenderest of the spring vegetables are already with us, together with a number of tasty and nutritious plants and fungi that can be found by the determined all winter long.

Let’s see if I can tempt you outside to track down and gather some nutritious winter wild food…

CHICKWEED, Stellaria media, can be found all through the winter and in fact is probably at its level best in winter and early spring. The tender tops of the plant make the best vegetable while the lower portion of the stems can be a bit tough and stringy. I eat the whole upper portion of the plant and the leaves from lower down. Chickweed (see photo) has one very distinct identification feature which will soon turn you into a chickweed expert when it comes to finding this plant. The stems possess a SINGLE row of hairs along one side only. Every time the row of hairs reaches a nodal point (where the leaves and shoots emerge) it moves around the stem by one-quarter turn before continuing on. This subtle feature is actually very easy to see if you hold the plant up so that it is silhouetted by the sky behind.

close up showing the distinctive single row of hairs

…chickweed is not only one of our commonest wild vegetables, it is also one of the most delicious! It can be enjoyed as a tender and flavoursome salad plant, or made into a somewhat iconic winter soup. I like to add a smaller proportion of another good wild winter vegetable – the red dead-nettle, Lamium purpureum, when I make my chickweed soup.

Here is the recipe.

WINTER CHICKWEED SOUP RECIPE (Serves 2 to 3)

Half a dozen small potatoes – washed but not peeled; chopped into small chunks

3 shallots

2 cloves of garlic

salt and pepper to taste

3 large handfuls of washed chickweed herb

2 large handful of red dead-nettle tops

As soups go this is about as simple and easy as it gets. It is truly delicious though and full of winter vegetable cheer!

Chop the shallots and garlic, and gently saute them in a little extra virgin olive oil until they begin to lightly brown then remove them from the heat.

Add the shallots, garlic and chopped potatoes along with a pinch of salt and a grind of pepper to a small saucepan with just enough water to cover them. Bring them to the boil for a minute or so then and turn down the heat to a low simmer. Add the chickweed herb and red dead-nettle tops and stir frequently. Keep checking to see if the potatoes are cooked. When the potatoes are soft you can either blend in the pan or transfer the whole mixture to a blender. The soup, once blended together, has a wonderful body and is thick and creamy. Season to taste with salt and pepper and serve at once with crusty bread!

Perennial wall rocket, Diplotaxis tenuifolia

PERENNIAL WALL ROCKET, Diplotaxis tenuifolia, is another good winter plant to look out for. This plant with small four-petalled yellow flowers survives quite well through the winter though it may not look its level best in the coldest of weather. The leaves look a lot like the kind of rocket that you can buy in salad bags from the supermarket and the flavour is about the same too though a little bit more spicy! This picture was taken in late December… in the middle of winter you will need to pick through the plants a bit to find the best leaves, but they are truly delicious!

COMMON or GREY OYSTER MUSHROOM, Pleurotus ostreatus, frequently fruits during the middle of winter. The chillier weather of December brings good pickings of one of the tastiest of all mushrooms, the FIELD BLEWIT, Lepista personata, although these are rarely found much after the beginning of January. January however is the peak time for a tasty bright orange-yellow mushroom that grows on dead and decaying trees and stumps…

VELVET SHANK, Flammulina velutipes, grows in dense clusters and the stems are covered in a brown velvet down over the lower portion. The gills are pale cream in colour and are not attached to the stem. There is also no evidence of a ring of any kind on the stem. These mushrooms are widely cultivated throughout Asia and you may have even come across them for sale in supermarkets in the UK under the name of ‘enoki’ or ‘enokitake’. The cultivated enoki has a much smaller cap and is wholly whitish, which means that it does not actually look as if it is the same mushroom as the wild one, but it is!

Velvet shanks are really worth going out to find. Old hedgerows, the edges of ancient trackways and green lanes make the perfect foraging spot for this prize and you may have to poke about in the hedge bottoms a fair bit on order to spot the half-buried orangey clusters of mushroom caps growing from the deadwood at the base of hedging shrubs such as field maple, hawthorn and wych elm. They are not too fussy however and I once even found a cluster growing from the base of a leylandii conifer hedge at the bottom of someone’s garden! Just be sure not to eat any that you find growing from yew as it is possible that they could have taken on some of the toxicity found in that majestic tree. They are probably fine but just to be on the safe side…

A walk around the field margins and woodland edges at the moment will turn up quite a number of food plants to experiment with. The youngest of CLEAVERS are up and if they grow in your area then young ALEXANDERS are available too. Both are delicious steamed and served with a knob of butter however It is best not to attempt to eat cleavers raw as the tiny hooked hairs that cover the plant can be somewhat scratchy to the throat. JACK BY THE HEDGE, also known as GARLIC MUSTARD, has actually been up for some time and its early tender basal leaves tasting of both mustard and garlic are just right for an al-fresco sandwich or to garnish a dish of cooked potatoes.

So… walking boots on, hand baskets at the ready! There really is no need to stop foraging just because it is the middle of winter and it can be very rewarding indeed for those who take the effort to go out and look. I hope you have enjoyed the few pointers that I have given to get you on your way but there is no substitute for direct experience. Have a happy and nutritious winter foraging adventure!

Place the mushrooms, elderberries, ginger, wild garlic buds and black pepper in a large Kilner jar or other similar storage jar. Mix together the warm water, cider vinegar and sea salt until the sea salt is completely dissolved. Pour this liquid brine over the solid ingredients in the storage jar, stir with a wooden spoon and allow the whole to marinade in a warm place for 2 hours.

Place the mushrooms, elderberries, ginger, wild garlic buds and black pepper in a large Kilner jar or other similar storage jar. Mix together the warm water, cider vinegar and sea salt until the sea salt is completely dissolved. Pour this liquid brine over the solid ingredients in the storage jar, stir with a wooden spoon and allow the whole to marinade in a warm place for 2 hours.

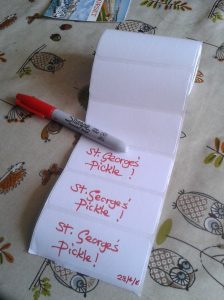

Always remember to label your produce carefully. Everyone must have found an unlabelled jar at the back of the cupboard at some point – with unknown contents that are probably well past their best. Always put the date of manufacture on the label.

Always remember to label your produce carefully. Everyone must have found an unlabelled jar at the back of the cupboard at some point – with unknown contents that are probably well past their best. Always put the date of manufacture on the label.