With St. George’s day in England just passed, and the festival of beltane / May day almost upon us, we turn our thoughts to the rapidly emerging vegetation all around and the appearance of spring mushrooms! First though, lets take a preamble through some of the foliage-festooned folklore that is associated with this time of the year. The themes that crop-up are held in common across much of Europe, Asia and India too…

St. George’s day (23rd April) heralds the beginning of spring revelry. The Catholic St. George was a graft onto older stock and this slayer, or perhaps befriender, of dragons is found throughout Europe, the near east and Russia today as both a protector spirit and a patron saint. In earlier times he often took the form of the ‘green man’, representing the rejuvinatory power of spring and the mysterious balance of light and dark, growth, decay, winter and summer that is central to the farmers’ and the foragers’ year. In Orthodox Christianity as well as in Russian folk magic and even among the shamanistic people of Siberia, the protector George is often called upon for strength and luck, and consulted and prayed to before going ahead with any major undertaking.

The Green Man

– by Grinagog (grinagog.deviantart.com)

Al Khidr, the Green Saint of Islamic folklore is perhaps another guise assumed by George, or perhaps more accurately another echo that has flowed on down to us via that same ancient river of belief.

In the holy-land, St. George, Al-Khidr and Elijah are commemorated together at the same shrines (for example in Bethlehem and Jerusalem) bringing the three major faiths of that land into the same places of worship. Similarly, in parts of India the cult of Kwaja Khadir, another ‘Green Man’, is observed by both Muslim and Hindu. His cult centre is at Bhakar near to the Indus river bordering India and Pakistan

.

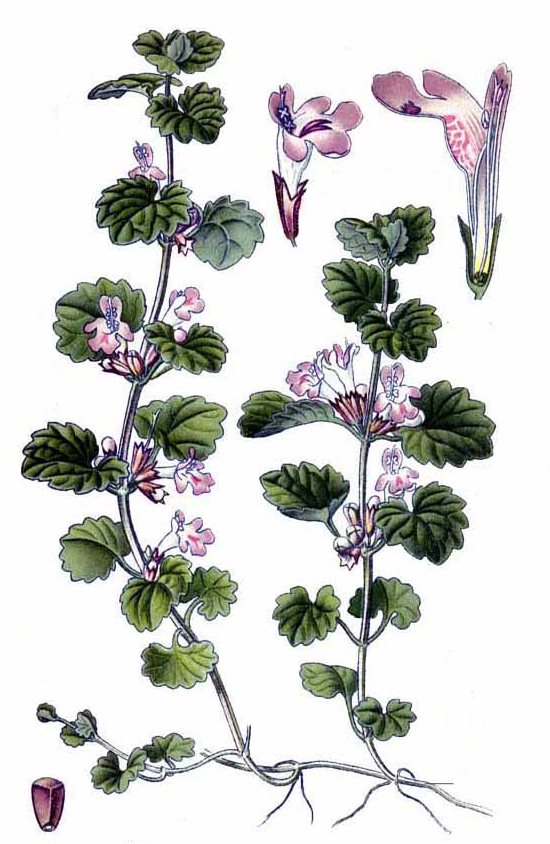

In some areas of south-eastern Europe the festivities of Green George (Gergiovden) are marked by decking a young man in foliage resembling very much the more modern Hastings Jack in the Green… and often he is paraded through the streets prior to being given a good ducking in the village pond or local river. In Bulgaria, Gergiovden is one of the biggest cultural holidays accompanied by many folk rituals for obtaining health and fruitfulness for people, animals and fields alike. As in the May Day festivities held in Edinburgh, Scotland, it is customary to bathe in the morning dew at dawn, as this is thought to bestow health and beauty for the coming year. Herbs harvested at this time are thought to have particular potency for healing. This festival is very popular in many regions of south-eastern Europe, especially among the Romani, taking place over the feast of St. George as reckoned before post-mediaeval calendar adjustments subtracted 14 days; meaning that it takes place on the 6th of May rather than the 23rd of April.

Very soon, in English fields and meadows, it will be time to make May garlands and walk among the wildflowers of spring purely for pleasure and contentment. In the folk customs surrounding our old May-day the ‘Green One’ will be readied to marry the May Queen, his bride, at beltane. In England too we have our own ancient traditions to commemorate his life, as in the (probably now a bit garbled) Padstow Obby ‘Oss song…

“O’ where is St. George, O’ where is he O’?

He’s out in his long boat, all on the salt sea O’.

Up flies the Kite and down tails the lark O’

Aunt Ursula Birdhood, she had an old ewe

and she died in her own Park O’”

St. George then, is possibly the embodiment of an ancient idea, heralding the return to intense growth and all acts of fertility in the wheel of the year. Some might suggest he is an ancient spirit remembered through folk tradition, that is perhaps older than the religious perspectives that we hold today. In Christian mythology we learn that he could not be killed until his body was broken on a wheel of swords, ground to dust and scattered out onto the land, where it would have provided fertiliser for the next cycle of growing and harvesting, and so, in contemplation of these cycles of time and of the year, I like to take a walk out into grassy meadows and limestone woods to seek the plump creamy-white fruiting bodies of St. George’s mushroom. I take this as a sign given forth by the earth herself to warn us that night-time frosts should now be a thing of the past and for her foragers it is time to be industrious in both field and hedgerow. This… is my personal ritual.

Calocybe gambosum – St. George’s mushroom

St. George’s mushroom, known in France as mouserron (a word that seems likely at the root of ‘mushroom’), smells pleasantly like new flour, as if it were freshly ground at the miller’s wheel. It often occurs in large rings in the turf. Remember: St. George himself was said to have been ground into flour or ‘broken on a wheel’ at his execution and spread upon the land by his Roman captors, as commemorated in the lines of the old English mummers play featuring St. George; “I’ll grind yer bones to dust and send you to the Devil to make mince pie crust”.

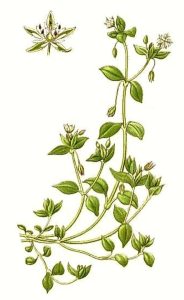

St. George’s, chickweed and dandelion blooms are a perfect combination in April & May!

It should almost go without saying, that you must be careful with your identification skills as there are some other whitish mushrooms that are very poisonous, though not many of them put in an appearance so early in the year. St. George’s mushroom is very tasty and highly prized and sought after in Italy and France. In Britain it has undergone something of a revival in recent years and it is to be found on the menus of many of the better restaurants and gourmet pubs. It can be sautéed in butter and goes well with shallots, asparagus, bacon, eggs and dandelion blossoms. It can also be pickled. The delicate complex flavour is easily overpowered by bolder ones and this is a mushroom to use as the feature of a dish, not a side portion, so take some care about who or what you partner it with.

A warm tossed St. George’s salad

Also highly prized at this time of the year are the elusive morels, often appearing in limestone woods and on sandy soils during the spring. The caps of these fungi, (there are several species) have an irregular honeycomb like appearance and the cap and stem are hollow. They are difficult to find but highly regarded as a cooking ingredient.

Morchella esculenta – Edible morel, and very tasty it is too!

Morels should be dried for storage and re-hydrated using warm water, herbs and a little salt for half an hour or so before cooking as this improves their flavour considerably. They go well with cream based sauces and add something very special to many dishes. Fresh morels can also be stuffed – one popular recipe uses crab meat, egg, mayonnaise and breadcrumbs – and baked for 15 minutes at 180°C. Be sure of your identification and do not confuse them with the poisonous gyromitra or false morel that looks a bit similar.

Oh… and NEVER eat morels raw or hover over the steam when you are cooking them, as just occasionally this has caused serious poisoning! Like most wild mushrooms, morels are not edible when raw and for the first few minutes, the cooking steam is not good for you either. It contains monomethylhydrazine, a component of rocket fuel, albeit in far smaller quantities than in the dangerous false morel (Gyromitra) species. Better to be safe than sorry. Step away from the pan for the first five minutes and let the steam be given off!

If you’d like to learn to find your own spring plants and mushrooms for the table, I’d LOVE to meet you on one of our Foraging Discovery Days!

Other links:

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khidr

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_George#Interfaith_Shrine

I have been taking people out to forage for spring cures for many years, and I look forward very much to making my own spring cure at this time. It is not essential to use all seven herbs, and substitutions can easily be made, but be sure to stick to stinging nettles for the base.

I have been taking people out to forage for spring cures for many years, and I look forward very much to making my own spring cure at this time. It is not essential to use all seven herbs, and substitutions can easily be made, but be sure to stick to stinging nettles for the base.

FEATURES: .

FEATURES: . FEATURES: .

FEATURES: .

CAP: Yellowish brown to reddish brown… but predominantly brown, looking just like a bread bun on a short, swollen fat stick – hence the name ‘penny bun’. Often there is a paler margin around the edge.

CAP: Yellowish brown to reddish brown… but predominantly brown, looking just like a bread bun on a short, swollen fat stick – hence the name ‘penny bun’. Often there is a paler margin around the edge.  STEM: The stem of the cep can be very very fat indeed, often with more usable flesh in it than the cap itself! The upper stem surface is covered in a very fine, pale/white, raised fishing-net pattern or ‘reticulum’. This white fishing reticulum is a distinctive feature.

STEM: The stem of the cep can be very very fat indeed, often with more usable flesh in it than the cap itself! The upper stem surface is covered in a very fine, pale/white, raised fishing-net pattern or ‘reticulum’. This white fishing reticulum is a distinctive feature.